Chapter 9 - Locked Down, Opened Up

The Hollow Bell — A serialized memoir, published chapter by chapter

< previous · next

table of contents

They took my street clothes. My shoes. Even my thoughts felt confiscated.

The hospital gown barely reached my knees as I stood blinking under fluorescent lights. A blur of paperwork, questions, forms. Then I was shown to a room with gray linoleum floors, two low metal cots, and one roommate.

He didn’t speak. Just shuffled in slow circles, drooling—one long, impossible strand swinging down to his knees like a pendulum. The kind of shuffle that doesn’t come from choice but from Thorazine—heavy, blunt, numbing. A pharmaceutical muzzle.

Whatever revelations I thought I’d been blessed with had no currency here. The light wasn’t gone. But it wasn’t welcome.

One woman stood out. Phyllis.

She looked like someone’s aunt. Soft face. Slippered feet. But there was something off in her eyes—foreign.

I remember her sprawled on her belly, across the threshold of her doorway, one arm reaching toward the ceiling lights. Her hand was twisted unnaturally, as if grasping for something only she could see. Her face was tilted upward, eyes locked on the fluorescent glow.

And then—still reaching—she evacuated her bowels and bladder. It seeped beneath the edge of her gown. Her expression never changed.

Something in me recoiled. And something else just… stilled.

Nobody reacted. Patients walked by as if it weren’t happening. A surreal silence gathered in the hallway, heavy and dissonant.

And then something cracked.

The silence wasn’t stillness. It was disconnection—the kind that seeps into your bones if you let it. I thought: If you weren’t crazy before this place, you’d lose your mind trying to survive it.

That was the moment I stopped reaching past the stars and started learning how to survive gravity.

Not sanity exactly. Just strategy. If I wanted out, I needed to play the game.

Johnny didn’t help.

He was my age, angelic face, dark curls, too much light in his eyes. I must have shared a bit of my psychedelic gospel with him, because the next thing I knew, he was telling everyone I was Jesus. Resurrected.

When I sat down with the supervising psychiatrist, he looked at me gravely and said, “So I hear you think you’re the son of God.”

I clarified. Politely. Explained that this was Johnny’s delusion, not mine. The psychiatrist nodded, half-convinced. I was learning: be coherent. Humble. Contained.

A social worker explained my rights. I could file a Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus. After 72 hours, I could appear before a judge. If I wasn’t deemed a danger to myself or others, they’d have to let me go.

So that became my plan.

I adopted the mantra: No harm to self. No harm to others. Appear normal.

I smiled. I nodded. It worked.

I had fallen through the crack, and the universe was still unfolding. But I couldn’t follow it.

I needed safety.

On the third day, I was moved to the voluntary unit. Brighter rooms. Access to the courtyard. A bit more air. A few days later, I was discharged.

Outside, the sun was blinding. The world no longer shimmered. I felt displaced—like a returned astronaut, reentering a planet that had moved on.

I called my friends. Nobody answered. Eventually, I found a cab.

When I got home, the reception was cold. Faces tight. Doors half-closed. No one said it directly, but I could feel it: I had become the person no one knew how to hold.

And the truth was, I didn’t know how to hold myself either.

The magic had gone. Colors dulled. Insight turned to static. I felt ashamed. Disoriented. Adrift.

I took the remaining tabs of acid, still wrapped in foil, and threw them into a construction dumpster just down the street. I told myself I wouldn’t go back.

A week passed.

The emptiness returned. Not boredom. Emptiness.

I started to wonder if the foil was still there. If maybe, just maybe, the universe would receive me again.

I walked barefoot down the street under a moonlit sky. Climbed onto the lip of the dumpster and peered inside. There it was: the packet. Shining beneath a broken plank of wood.

I took it.

The trip wasn’t as intense. But the crash afterward was worse. I could feel my grip loosening, my thoughts unraveling into threads I couldn’t gather. I wasn’t chasing revelation. I was trying to outrun the grief of losing it.

The next morning, I was sitting on the living room couch. My roommates were buzzing around, anxious. Then I heard the front door open. The police.

I froze. But I stayed still. Calm. Remembered my script.

“No harm to self. No harm to others.”

The officers questioned me. I smiled. I answered. After a few minutes, I heard them tell my roommates, “There’s really nothing we can do. Try to get him to a doctor.”

That evening, the last of the LSD wore off. And with it, the illusion of control.

I looked at what I’d done. What I’d become. It felt like the universe had unraveled in my hands, and I was left holding threads that led nowhere.

Then the phone rang. It was my mother.

Her voice cracked with pain. She said she was coming. That she’d fly out. That an ambulance would take me back to the hospital.

And I said okay.

This time, I was admitted into the voluntary unit. There was a courtyard with trees and benches. I sat in the sun. Drew animals in art therapy. Joined group discussions. Tried not to think too much.

A few days later, my mom arrived. I saw her across the visiting room. Pale. Focused. When we locked eyes, something softened. We hugged.

She didn’t try to fix me with words. She just got to work. She packed up my things. Stored my car. Managed insurance. Called the university. Arranged care in New York. She did what moms do when the world falls apart.

Toward the end of my stay, a girl came to visit me.

We’d met during the height of my altered state—dinner, one long evening, that was it. I had shown up to the café where she worked barefoot, speaking in metaphors and awe. I was spinning. And yet, somehow, something in me must have landed.

Now here she was.

Golden hair draped over her shoulders.

Soft green eyes.

Sun-speckled cheeks.

I barely knew her. We’d barely spoken since that night. One call, maybe. And still—she showed up, as if something had sent her.

When she walked in, something in me opened.

A petal, unfolding.

Tender. Soft. Sweet.

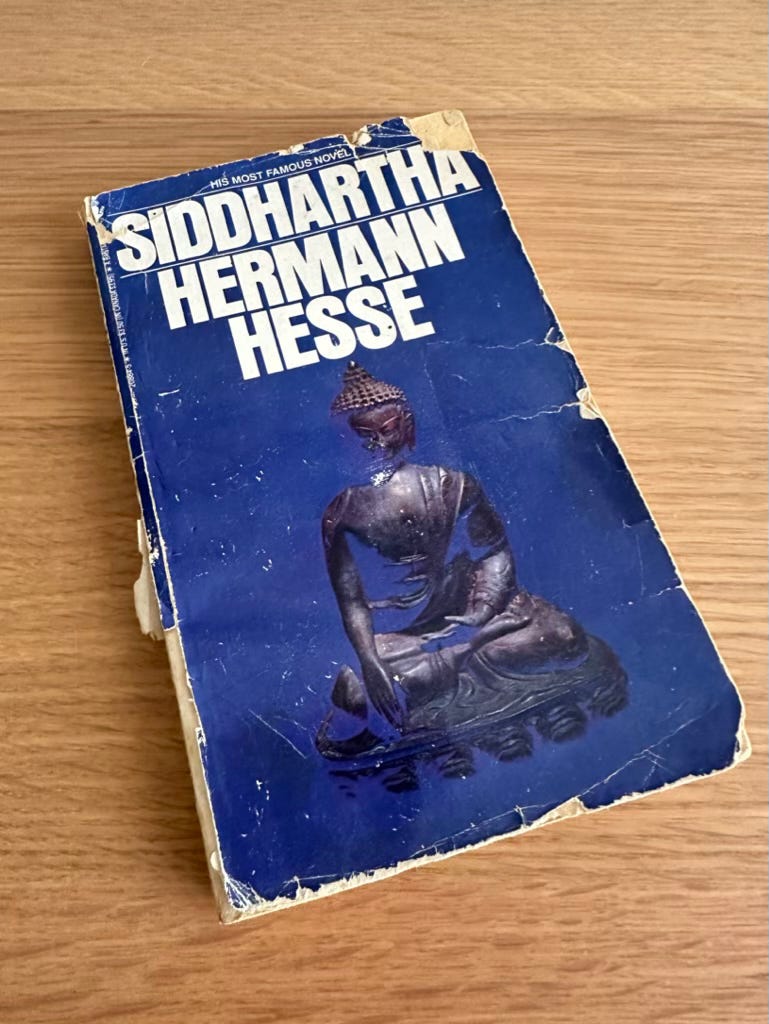

She brought a small, dark blue book.

She paused before handing it to me.

Siddhartha.

She said her brother had given it to her, and now she wanted me to have it. A gift passed without commentary.

Without knowing.

I didn’t realize then how much that book would matter. But it was the first time I held a story that felt like it knew something I didn’t.

Not the details. Not the plot.

Just a quiet gravity.

Like something deep inside had clicked—

a recognition I couldn’t explain.

A knowing that hadn’t reached the surface yet.

I thought she was the flower.

But it was the book.

Small. Quiet. Unopened.

A seed disguised as a gift.

I didn’t know it yet, but my whole life had already unfolded there—gently hidden between the riverbanks and the letting go.

And now, decades later, I can see it clearly.

I wasn’t just holding a book.

I was holding the outline of the life I would come to live.

In a way, I’ve spent nearly forty years rewriting Siddhartha.

But I couldn’t see that then.

I didn’t recognize the path.

Not yet.

Many readers have told me they set aside time for each chapter, letting it echo into their own lives. If the bell rings in you, consider passing it on—someone else may be listening for the same tone. And if you’d like, leave your reflections below; your voice adds another note to the resonance.

I am thinking about who I want to share your posts with. Maybe one of my longest connections with writing. I'll know as I ponder further. In the meantime this was something that stood out to me: "I was learning: be coherent. Humble. Contained." I wonder if that line was a special message I needed today. Thank you.